| ROK's and Shoals |

| Spring and Summer 1967 |

| Hon Heo - Mui Batangan |

|

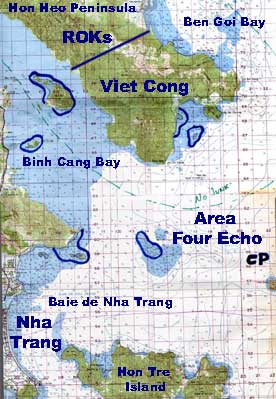

Looking back after thirty-five years, it is a remarkable co-incidence that two of the patrol areas where PCF 45

operated, widely separated both geographically and in time during 1967, were in close proximity to coastal land

sectors where the relatively few Republic of Korea (ROK) forces participating in the conflict held primary

responsibility. One was north of Cam Ranh Bay and Nha Trang, and encompassed Ben Goi Bay and the area up through

Vung Ro. A ROK unit was conducting land operations in the adjacent coastal region. When we relocated a few hundred

miles north to Chu Lai, our primary assigned patrol areas included the coast and rivers just north of Quang Ngai,

where a different ROK force operated.

The ROK forces very much deserved their reputation as fierce and dedicated warriors. However, our interaction with

these forces during joint operations could not always be considered as being successful. And, in at least one incident,

the experience left a disturbing taste in the mouths of the Swift Boat sailors involved

|  |

| Our first encounter with ROK forces ocurred shortly after our arrival in country to operate out of Cam Ranh Bay. The ROK's had "bottled up" a large Viet Cong force by sealing off the northern entrance to the Hon Heo Peninsula north of Nha Trang, and were moving down the peninsula to engage this enemy unit. Coastal Division 14 Swift Boats were tasked with forming a blockading ring around the peninsula to prevent any of the enemy from escaping by water. The small draft of our boats was particularly useful in the shallow upper regions of Binh Cang Bay west of this long land mass. The blockade was apparently successful, in that no movement of the enemy by water was detected during the operation. However, on the third day after contact was made with the VC, the ROK forces called a two-day halt to their activities in order to celebrate an important Korean holiday. During this two-day "cessation of all hostilities", the enemy forces simply donned civilian clothes, passed through the ROK lines, and melted into the general population north of the peninsula. When the operation resumed, the entire area was devoid of any Viet Cong activity or presence. Pretty frustrating to all concerned. |

At the end of February 1968, a North Vietnamese re-supply trawler crammed with arms and ammunition was forced aground

at the southern tip of Hon Heo and self destructed in a violent explosion.

The other frustrating incident involving interaction between our Swift Boat and ROK forces occurred south of Chu Lai

on the northern shore of Mui Batangan, a prominent peninsula jutting out into the South China Sea north of the Song

Tra Khuc river which leads inland to the city of Quang Ngai.

|

This area was, and continued to be throughout the war, very active with a unit of the North Vietnamese Army using it as a base of operations. It was not far from the entrance to the Tra Khuc that the infamous, and very sad, incident at My Lai took place a few months after we were there. And, much later in early 1970, a US Army Lieutenant Colonel by the name of H. Norman Swarzkopf would lead a battalion of the Americal Division in successful operations in this area. He is reputed to have labeled Batangan a "bad ass place". The Swift Boat sailors that operated near the coast line and in the river mouths there would certainly agree that this was an apt description. |  |

The next four sections of this web site describe events which occurred during 1967 in the area seen from this aerial image. We did try our best to maintain a sense of humanity while dealing with the violence occurring on the peninsula, but sometimes events were simply beyond our control .... |

|

During the summer of 1967, the ROK Marine forces were conducting an air and ground assault on the coastal village of

Chau Thuan, situated about halfway out on the northern shore of the peninsula ... in the lower left hand portion of the

above image showing Mui Batangan and pin pointed on the map in the slide show. This involved air strikes by helicopter

gunships and fighter bombers on the village and its surrounding area.

The Swift Boats were again tasked with laying just offshore of the north side of the peninsula to prevent any enemy troops

from escaping by sea.

|

|

As can be seen from the accompanying images taken at the time, the air units were giving the area a terrific pounding. |

|

|

|

|

Human nature being what it is, it was not surprising that a good portion of the village jumped into their fishing sampans and moved about a mile offshore to escape the destruction that was raining down on their homes. |

We were soon engulfed in a large fleet of such vessels, occupied by very scared old men, women, and children. They quietly and politely remained anchored, waiting for this hellish turn of events to be over. Using the Vietnamese Navy Liaison Officers on board, we, along with the 79 boat, inspected as many of the sampans as we could to insure that no suspicious persons, activities, or material were located on these vessels. Our VNN interpreter assured us that these villagers were indeed "non-combatants". |

|

There was no way to determine if these people had sympathies toward the communist north or not. Most likely they were caught in the middle of a conflict they did not understand, and were hoping that both sides would just leave them alone to continue their long term existence in the area. After we had completed our inspection, and continued operating as close as prudence dictated to the on-going air assault, we received radio communications from the ROK officer in command of the operation flying overhead in a helicopter. He ordered us to "move those damn people back into the village where they belong". We tried to convince him that the Vietnamese in the sampans were not about to return to their village while it was being blown all to hell and gone. We had them under close supervision, and they posed no threat to his operation. But he continued to insist This semi-stalemate continued until there was a cessation in the air strikes. We also got "guidance" from our controlling base station in Da Nang indicating that we should probably do what the ROK officer wanted. Since the immediate threat seemed over with, we put the VNN interpreters on a bullhorn and began encouraging the people in the sampans to return to their village. We even fired several rounds of M-16 fire into the water to emphasize the need for them to proceed back to shore. After a while, they all did indeed head back. It was a little like herding cats, but we followed them in until they were close to their village. The ROK officer was satisfied. As the sampans were arriving at the shore line, the relief Swift Boats for the 45 and the 79 arrived from Chu Lai. We briefed them on what was going on, and began preparations for returning to base As we headed north, we looked back, and to our amazement and disgust, the air strikes started up again. Large explosions billowed up from the village where the sampans had just landed. No one knows if any reports of "KIAS" resulted from this second pre-meditated assault, but it would not have been a good time to be present in that village. The trip back to Chu Lai was a depressing one. As Ed Bergin later put it: "The smell of cordite from helicopter guns and the air bombs now became mixed with the foul taste of kimchi". One pondered if conducting the war in this way would really accomplish our goals and purpose for being there.

|

|

|

One of the more significant "lessons learned" by the US Military during the South East Asia conflict, which has been applied in operations since then, was to place a top priority and major emphasis on proactive measures to prevent, or at least minimize, casualties to civilians and other friendly forces.

The following first person account was provided by John Cavano, moderator for the

White River Shipmates

web site. USS White River (LSMR-536) was a rocket launching platform providing naval gunfire

support for US and allied land forces along the same coasts and rivers where the Swifts operated.

The story provides insight into the possible gross mis-intrepretations of the Rules of Engagement at the time which could

lead some commanders into decisions with tragic and abhorent consequences such as the above and at My Lai. Both

of these terrible incidents, and the White River story, all occurred in the same area.

But in LSMR-536's case, as John puts it at the end of his story: "Fortunately, I don't think we actually killed any friendlies that day."

|

|

|

In 1968 the White River almost blew a US Swift Boat out of the water. It was a typically hot, clear morning and we were on a routine cruising mission steaming up and down the Vietnam coast in our normal operating area. I was just getting near the end of my watch when we cruised by a beach area with a huge mass of sampans and people in black pajamas. I notified the CO of the sampans and people and was at the same time relieved by the next Officer of the Deck. The CO came up to the bridge shortly after the watch change and ordered us to return to where I had spotted the mass of Vietnamese sampans. During this return trip, a matter of 10 or 15 minutes, we checked with our land based operational command and verified that these people and boats were in a designated "free fire zone" and consequently, anyone in that area was considered to be "unfriendly." The CO called GQ and I returned to my GQ OOD position to take the ship into a firing position. Someday, I will be able to fully understand the feeling I then had knowing we could be setting up to kill what appeared to be hundreds of people right in front of us. Suffice it to say, to this day, it is a disturbing feeling to recall. We took a position about 2000 yards from the mass of people and sampans and followed our usual procedure of "bracketing" the target. We were firing at what we thought were VC in a "free fire zone." After a long shot that went up on the beach, and a short shot that landed between us and the floating mass, the next one would have been right in the middle of a group of sampans and people in black pajamas. |

|

|

|

As you can well imagine, with each rocket, more and more of the mass of people and boats began to disperse. Gradually, there, in all its glory, was a genuine US Swift Boat. Our bridge radios were going nuts and I heard our call sign "Jiltfoxtrot, Jiltfoxtrot, this is {Swift Boat call sign} interrogative your intentions" I rushed out on to the bridge wing and pointed the CO's attention to the rapidly thinning mass of people and sampans. I think he saw the emerging Swift about the same time as I did, called a cease fire and also ended our GQ! The following PCF Swift Boat looks a lot like the craft we saw. This image gives you an idea about what we saw and didn't see. The CO was absolutely livid and got on the communications net and asked the operational command just what the heck was going on! There was quite a lively exchange of dialog. White River was cleared of any error and it became a matter for the operational command people to resolve. Fortunately, I don't think we actually killed any friendlies that day.

|

|

|

|

This web site is Copyright � 2002 by Robert B. Shirley. All rights reserved. Click on image to return to the homepage

|