| ! Misfire ! |

| Song Cho Moi / Sa Ky River |

|

For information on the development of this unique weapon, view Bill Wells' The Coast Guard's Piggyback 81mm Mortar / .50-caliber Machine Gun |

Our Swift Boat crew was among the “second generation” to be formed for service in Vietnam. The first boats had been

deployed starting in late 1965 and throughout 1966. So, as we went through “boat school” at Coronado in January of 1967, the

experiences of the earlier crews involved in the first deployment were incorporated into our training.

One of these was the unfortunate, and very heart rendering, incident involving PCF 9 in which an 81 mm mortar round

had exploded in the breach of the “naval gun” on its fantail, killing three crewmembers, injuring two others, and

doing extensive damage to the boat. Needless to say, the reports of this incident had a chilling effect on our

attitude toward this weapon. Additional safety procedures to be used in dealing with this relatively new piece of

equipment were quickly added to the training program.

|

As seen in the lead-in image to this section, the “naval gun” installed on all Swift Boats and Coast Guard WPB’s during operations in Vietnam was an “over and under” arrangement of a .50 caliber machine gun and a unique configuration of mortar tube. The gun was loaded from the front end, in the same way as a land mortar. But the firing pin at the bottom of the tube was retractable, allowing the round to rest at the bottom of the tube and the weapon to be fired at any elevation angle. The gun could be aimed for direct fire by swinging the tube/machine gun on a two-way swivel before pulling the trigger and causing the propellant charges, arranged in plastic bags around the fins of the mortar, to send the round on its way. |

|

Our crew’s somewhat cautious attitude toward the mortar carried over to our initial few weeks operating out of Cam Ranh Bay. But we were soon called upon to provide both illumination and indirect fire support to some of the more remote land units along the coast beyond the normal range of artillery units. So we very quickly became familiar with the gun’s operation, reasonably skilled at providing indirect support, and also comfortable that the weapon presented no unusual safety hazards when operated with caution. But the recollection of the PCF 9 incident was never very far from our minds.

|

|

|

The procedure we developed to provide indirect fire support in the darkness of night, when reference could not be made to visible land marks, was as follows: We would use data provided in printed tables to determine the number of 81 mm propellant charges, combined with a specified elevation of the tube, needed for the round to travel a set distance; typically several thousand yards. The gun would be raised to the determined elevation, locked in place pointing 90 degrees from the heading of the boat, and the mortar round loaded. The crew member in the pilot house would set the radar cursor to 90 degrees, observe the land mass on the radar, and using the throttles of the twin screws of the boat, jockey the heading of the boat until the cursor and the range rings on the radar indicated that the weapon was aimed where desired. He would then use the sound powered telephones to tell the men at the gun to fire. It was surprising how accurate this rather primitive method of “gun laying” could be. |

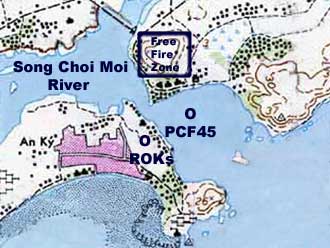

| And then came the following incident in the Song Cho Moi {aka Sa Ky} river of the Batangan peninsula south of Chu Lai during the early summer of 1967. It may seem somewhat humorous in retrospect, but certainly was not so at the time. And could have had deadly consequences as described further down this page. Our boat was tasked with providing “harassment and interdiction” support to a Republic of Korea (ROK) unit entrenched for the night on one side of the river. We were to proceed up the river at periodic intervals and fire a few rounds into an uninhabited “free fire zone” designated by the ROK’s. |

| A rather simple assignment that did not seem to hold the potential for any surprises. |

The first vestiges of the northern monsoon season were evident that night, with totally overcast skies and turbulent seas outside the protection of the river. It was probably our complacency that got us into trouble. The 81 mm mortar rounds were stored in the ready service locker on the extreme end of the fantail (Seen in the image at the top of this page). We would remove the rounds from their plastic wrapping and cardboard containers and place them in this locker, making them readily available for immediate use as we entered the river to fire our next set of rounds |  |

This process was repeated several times as we randomly entered the river to fire

our rounds into the barren hills overlooking the small enemy held village and

then departed the protection of the high ground to return into the choppy waters

of the South China Sea.

However, the top of the ready service locker was not completely water tight,

so it is relatively certain that some seepage of seawater got onto the

rounds during our time outside the river.

Very late at night, in complete darkness, the following dialog took place over the sound powered phones between the

pilot house and the gun ... as best as the language can be recalled ... as we once again came to a stop opposite

the ROK position in the river.

“First round loaded”

“!Fire!”

!!BAM!!

“Second round loaded”

“!Fire!”

Phfzzzzzzzt

“Jeez! ... What happened?”

“Dunno, all of us are crouching behind something, taking cover”

“Well? ... Did the round leave the barrel?”

“Christ, it is as black as a well digger’s rear end back here."

“Okay, guess we need to go through the sheet eatin' misfire procedures”

This involved one man raising the rear of the gun, banging it "gently" against the stops, while

another man stood at the front of the gun with outstretched hands waiting for the misfired round

to come out, grabbing it before it fell

to the deck, and then throwing it overboard !!!

The thoughts of PCF 9 were swirling through all of our heads.

After a very long period of pregnant silence:

Tap - Tap - Tap

“There aint no round coming out of that tube”

“Are you sure that the round is not stuck in the tube?”

“Hell, I don't have the foggiest gol dang idea!”

“Well, we just gotta make sure."

After a very, very long period of pregnant silence:

“Are you outta your frippin' mind?"

After a very, very, very long period of pregnant silence:

“Ok, I am in front of the gun with my flashlight.

Getting ready to look down the barrel.”

“What do you see?”

“!MAN! … IT IS REALLY SMOKEY DOWN THERE!”

And with that succinct and memorable remark, a slight smile and a collective sigh of relief

was emitted from all hands. We secured from the "drill," stowed the weapon, and discarded any

further attempts to provide H&I fire that night

The following morning revealed that the round had indeed left the barrel, probably landing unseen and unexploded in the

river a few yards between us and the shore.

|

|

Not all of the Swift Boat crewmen that experienced mortar failures were as fortunate as our crew in 1967. There were a

total of five misfires on Swifts that resulted in severe injuries and deaths to the sailors that had the misfortune

of being in close proximity to the weapon when a round unexpectedly exploded while still inside the mortar tube.

The following is an account of one of these tragedies that was suffered in late 1968 by the crew of PCF-89 while

operating out of Coastal Division 15 near Qui Nhon.

|

My name is Jerry Jones and I was a 22 year old Second Class Radarman serving with Coastal Division 15 in Qui Nhon Viet

Nam on November 8 1968. This is my narrative of the events leading up to and following the explosion on PCF 89 on that

night. The passing of the years may have clouded my memory and distorted some remembrances but I think that this is

pretty much what happened from my perspective

I was not a member of the original crew of PCF-89. I did my training with another crew and arrived in country shortly

after the Tet offensive in February of 1968. As a Second Class Radarman I was the leading Petty Officer of the boat,

with only about 2 ½ years of service. Also on my first crew was a Third Class Bosn's Mate with 12 years of service.

In August he made Second Class and, I guess because the OinC thought he was stricter and a tougher leader, he was made

Leading Petty Officer and I was given the option of leaving or staying. I decided to transfer.

Ltjg Richard Wallace's crew arrived in country in September with just three sailors that went through training with him.

John Wyatt and I were assigned to fill out this crew.

Therefore, as of October 1968, this was the crew of PCF-89: Ltjg Wallace served as the OinC; John Singleton was a First

Class Engineman and therefore the LPO (Leading Petty Officer); Pete Blasco was the Bos'n; I was Radioman/Radarman; John Wyatt

the Gunner's Mate; and Dave Mason the Quartermaster.

On the patrol of November 8, 1968 Dave Mason was sick so Stephen Volz was assigned to fill in for him. (One of those fickle hand of fate things I guess) Anyway, the patrol during the daylight hours on that day was fairly typical except that, as I recall, Pete Blasco had just gotten a letter from his wife and he was passing around a picture of his new baby. Other than that, it was the usual routine of patrolling the coastline, stopping a few fishing junks then boarding and searching anything larger that looked suspicious.

I then re-entered the Pilot House and made contact on the radio with the Army spotter. I also plotted our position from the radar and fed the distance and direction information to the target area back to Mr. Wallace, who was on the fantail with the 81 mm mortar crew.

We began to fire, but after a few rounds we discovered that the boat was drifting with the current because the anchor was pulling loose from the sandy and muddy bottom. The movement of the boat was causing our fire to creep closer to the Army's perimeter. They were warning us about it and we tried to adjust our fire. But the boat was drifting too quickly. Finally the spotter ordered us to cease fire. I relayed those instructions back to Mr. Wallace and he gave the order to cease fire. I ran up to the bow and dragged in the anchor as Mr. Wallace again worked the controls back aft.

I tore off the phones and ran back to the fantail. It was total devastation. The gun was totally gone from the mount.

The engine hatch covers had been blown completely off and were sitting diagonally across the openings. Volz had disappeared.

Mr. Wallace and Blasco were down on the deck and John Wyatt was sitting up against the mortar box. John Singleton and I were

both unhurt but badly shaken. We tried to take inventory of the injuries and remember our first aid training. As I recall,

we were supposed to look for sucking chest wounds, then severe bleeding etc. I knelt down over Mr. Wallace and his chest

was full of holes but none were sucking and there was not any bleeding visible in his chest area. His right leg and

part of his hip were just not there. Blasco was in similar shape but both of his legs appeared intact. John Wyatt had

wounds everywhere and one of his legs showed a horrific compound fracture. Despite that, he managed to remain sitting up.

All three were conscious but in a lot of pain and asking for help.

My first aid training went right out the window. I was totally overwhelmed and felt completely inadequate for a job of this

magnitude. John and I decided that all we could possibly do was give everyone morphine to kill the pain in order to make

them comfortable and keep them from going into deeper shock. At first we tried to take into account that there were some

wounds where giving morphine might cause a drop in blood pressure and cause further complications. But we figured that it

was already past the point of worrying about that. From what I was seeing, it seemed entirely possible that if much needed

serious medical attention, more than John or I could provide, was not available immediately, then all three would be lost.

John's leg really needed work but we couldn't find anything to splint it with. And quite frankly I knew I didn't have

the stomach to cause him the pain that trying to straighten it out would cause. We finally settled on morphine, blankets

and pillows to make all three more comfortable.

As we worked feverously to provide assistance, we suddenly realized that we could smell diesel fuel. The tanks were

leaking and the engines were still running. We quickly shut down the engines.

I don't know how long I was on the fantail before I became aware that there was someone trying to reach us on

the radio. With an incredible sense of relief, I realized that required help was indeed available. I just needed to let the

world know about the details of our disaster. I spoke to the base and gave them a report. They said a medevac chopper was

already preparing to get airborne and that they were scrambling a couple of boats to come to our assistance. There was also

a battleship in the area (the New Jersey I believe) and it was rushing down to provide protection in case we were attacked.

When the other boats arrived they put a couple of their crewmen aboard the 89 to assist us and then began slowly sweeping back

and forth with their spotlights illuminating the bottom hoping to spot Stephen. They were unable to find him that night.

It wasn't until the search was resumed in the light of the next morning that his body was discovered. The blast had

blown both him and large pieces of the mortar overboard.

After the helo departed, John Singleton and I took a deep breath and began to seriously participate in the search of

the waters around the boat for Steven Volz. When it was finally certain that further seaching in the darkness would be

fruitless, a tow line was passed over to us from one of the other Swifts. We pulled up the anchor and were towed the

short distance back to the Coastal Division 15 base in Qui Nhon.

I remained on duty with Swift Boats until March of 1969 when I left Vietnam and separated from the Navy. Even though I

can recall most things about that night and about what happened during my tour before then, I simply cannot

recall anything of my last four months in country. I seem to have pretty well blocked out everything after that night.

Earlier this year my Dad passed away and among his things I found some of my old letters home. One mentions my being

on another crew. But I don't remember any of that or the sailors I served with after November.

|

The following day, the fantail of PCF-89 was cleaned up of all the debris from the explosion and the following pictures taken to document the tragedy for possible analysis of what happened and to determine any lessons that could be learned from what had taken place. The images clearly indicate the magnitude of the detonation and the effects it had on the Swift sailors that were on the fantail at the time

Sadly, both Ltjg Richard Wallace and BM3 Peter Blasko passed away in the Medical Evacuation Hospital in Qui Nhon not long

after they arrived on the Dust Off helicopter. As indicated in Jerry's narrative, Stephen Volz's body was recovered

from the sea on the day following the tragedy.

John Wyatt survived. However he was to experience a very long period of additional treatment and re-habilitation in

hospitals near Seattle. He has never fully recovered from the injuries sustained to his legs on the night of November 8,

1968. |

This web site is Copyright © 2002 by Robert B. Shirley. All rights reserved. Click on image to return to the homepage

|