|

The loss of the first Swift Boat in the Vietnam Conflict

The crew of PCF-4 on February 14, 1966

Charles D. Lloyd, LTJG, Officer in Charge - WIA

Robert R. Johnson, RM3 - WIA

Jack C. Rodriguez, EN2 - KIA

Tommy E. Hill, BM2 - KIA

Dayton L. Rudisill, GMG2 - KIA

David J. Boyle, SN - KIA

| |

One of the certainties of war is that participants will want to bring home souvenirs. For a sailor this is

perhaps a legacy from an earlier era of naval heritage when it was common to award bounty to victorious crews after a battle.

But more likely, it is just a simple desire to have something tangible to show that "I was there." Something to hang on the

wall or place on the mantel back home so that visitors will ask the question that permits the veteran to indulge in one of

the few satisfactions about his wartime experience: explaining how and where he served his country.

| |

Another certainty of war is monotony. And monotony is an insidious enemy that quite often provokes complacency when

accompanied by physical exhaustion. This, in turn, can result in severe unintended consequences. On Valentine's Day

in 1966, these factors taken together descended upon a Navy Swift Boat on patrol in the Gulf of Siam and snow balled

into a tragic outcome.

| |

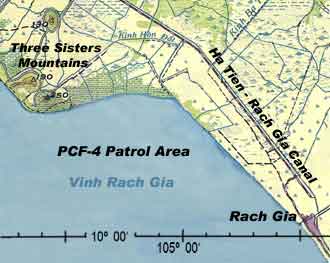

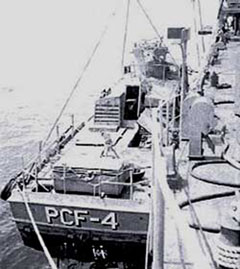

PCF-4 had been on patrol for many hours that day, only a few weeks since being one of the first Swift Boats to arrive

in Vietnam. This day was very similar to previous ones. They were patrolling, boarding, searching, and patrolling again. Scanning the dark

waters and green shorelines with tired eyes that blurred from long hours and little sleep, the result of constant stress

as the new boats were quickly rushed into service in an environment where the tasks and dangers were largely unknown.

Continuing to look for unusual activity, the Swift slowly proceeded just offshore in Rach Gia Bay, on the western coast

of the Mekong Delta. In the distance loomed three small mountains, which the Americans called Three Sisters, looking

formidable rising from the coast

| |  |

|

| |

In the late afternoon, a crewman spotted an object in the water fairly close to the shore. He reported

it to the officer-in-charge, Ltjg Charles Lloyd, who immediately ordered the helmsman to set a course to intercept it.

Through binoculars, Lloyd could see that the object appeared to be a small bamboo raft, empty except for a pole from which

flew a crude Viet Cong flag.

The flag certainly was a potential souvenir, but more importantly it represented a blatant challenge to the authority

of the Government of South Vietnam and its US ally. Lloyd decided that action was required to remove this symbol of defiance. The young

officer knew there were risks involved, so he ordered his crew to battle stations and then moved in very cautiously,

slowly circling the objective several times much like a predator evaluating its prey.

|

All things considered, the flag appeared to be nothing more than an exhibition of contempt by some zealous

supporters of the Viet Cong. But because Lloyd remained appropriately wary and suspicious, he ordered one of his crewmen

to toss some grenades at the raft. Several grenades exploded close to the little bamboo structure, causing the flagpole

to wave frantically for a few seconds - then nothing; no secondary explosions; no response from the shoreline where unseen

enemies might be hidden. All was quiet except for the rumble of the idling diesels on the Swift.

This situation was entirely new to Charlie. It had not been covered in any training he had received or in any of the

limited briefings given before going on patrol. Like many other examples in the previous weeks since the new command

had started operations, here was another case of breaking new ground with no prior experience to guide his decision

concerning what was a prudent course of action. He had exhibited extreme caution with no apparent indications of danger.

As a result it seemed reasonable to allow his curiosity to be satisfied concerning this offensive object.

Therefore he ordered his craft to close in on the bamboo raft. With the boat handling skills characteristic of Swift Boat

sailors, the helmsman eased the vessel directly alongside the raft so that the flag bobbed within arms reach of the rail.

A seaman reached out and grasped the pole. With his knife he began cutting the lashings while his officer-in-charge leaned

out of the pilothouse to observe.

| |

In the shadows of the mangrove trees on the nearby shore, a pair of eyes watched as the gray fish nibbled at the bait.

It was time to set the hook. Hands holding the wires of a crude but effective detonating circuit came together, allowing

bare copper to touch bare copper in deadly union. An explosion erupted beneath PCF-4, ripping into her underbelly. The main

deck buckled upward, crushing and trapping the helmsman against the overhead of the pilothouse; the gunner above was hurled

out of his gun-tub and into the water. The Swift, her hull torn open and her frame traumatized, plunged beneath the frothing

water almost at once and dug deep into the mud of the bay's floor. |

|  |

|

Lloyd was blown over the side and found himself underwater, disoriented while trying desperately to swim to the surface,

and as a result going sideways in the shallow depths. When he did get his head above water, he tried to find his other

crewmembers, but could only locate Bob Johnson and David Boyle. He also became painfully aware of devastating wounds to both of his legs,

but managed to maneuver back to the partially submerged wreck. Only the gun tub, mast and the hand rails on top of the cabin

area remained visible. Charlie told Johnson, who appeared to be less severely injured, to dive into the boat and try to

find a working radio. While the lieutenant clung to parts of the badly damaged vessel, Johnson reported that every

radio was smashed and all of the weapons were unusable.

Since Boyle appeared to be in the most critical shape of the three, the officer-in-charge had Johnson put him on the

boat's life raft and told him to move as far away from the shore and the boat as possible. Charlie continued to hang

onto the side of the wreck, used his belt to tighten a tourniquet around his badly bleeding right leg and kept a lookout

for any sign of activity in the vicinity. His left leg also had a compound fracture with bones sticking out and his left

boot was turned almost completely around.

| |

| |

Fortunately, a nearby South Vietnamese Navy Yabuta had been alerted by the noise of the explosion and rushed to the scene.

Although it seemed forever to the men in the water, it probably was only a few minutes before the Vietnamese sailors arrived

and were able to take Bob Johnson and David Boyle aboard from the life raft.

| |

At the same time, from his position on the seaward side of PCF-4, Charlie observed an enemy soldier swimming toward

the boat. Despite the pain in both of his legs, he slipped away from the boat and began swimming toward the Vietnamese

junk, using only his arms. The Vietnamese sailors also saw the enemy swimmer and used suppressive fire from their on-board

machine guns to prevent this obvious attempt to collect arms, ammunition or other material from the boat.

Once at the Vietnamese junk, Charlie was also hoisted aboard to join his two crewmen. Although his wounds were causing

him to fade into and out of consciousness, he managed to have the Vietnamese hand him their portable PRC-10 VHF radio.

He quickly dialed a new frequency and called in a Mayday report to the US Army Tactical Operations Center (TOC)

in Rach Gia. Along with Johnson, he also tried to look after David Boyle. But there wasn't much they could do to help

the young sailor. Things also went blank for Charlie at that point. He passed out. This time for a longer period.

Charlie's emergency radio call to the TOC was relayed to LT Gil Dunn, who was the Senior US Naval Advisor at Rach

Gia. He immediately called a local US Army helicopter unit and asked if they could assist with a search and rescue

operation. They were airborne within twenty minutes. The TOC also put out calls to any US military units in the area

that could provide expedited assistance to the damaged vessel and opposition to any further actions by enemy forces

| |

LT Dunn piled into a small runabout that had an outboard engine, along with an Army Medic and a Navy Chief Gunner's

Mate, and headed out of the harbor. They took along with them a first aid kit, an M-60 machine gun, and a portable PRC-25

radio. Once into the Bay of Rach Gia, they turned north and headed up the coast in search of the reported Swift in distress.

The increasing overcast and fading daylight did not bode well for the success of this tiny rescue effort. But Dunn was

determined and knew the area well. He drove onward toward the Three Sisters, racing to get there before the sun fell

entirely below the horizon. | |

| |

From the air, the Army helicopters spotted the broken hulk of PCF-4. They observed that she was almost completely

submerged. Only the very top of the pilothouse was still visible in the valleys of the swells gathering in a freshening

southern gale. The radar mast was protruding from the water as though the craft was snorkeling through it. They also

caught sight of the Vietnamese Navy junk with the three survivors lying on the deck. They contacted the Rach Gia

motor boat on the radio and vectored them to the area. Rach Gia's Operation Center communicators also had a Dust-Off

medical evacuation helicopter, PCF-3 and a US Coast Guard cutter on their way as well.

When the open boat from Rach Gia reached the scene, the officer and the medic climbed aboard the Vietnamese junk. LT

Dunn first went to David Boyle who was lying quite still. A check of his pulse produced negative results. While the medic

attended to Bob Johnson, Dunn moved on to the next man and was surprised to see that it was Charlie Lloyd. He had once

ridden on PCF-4 and he and Charlie were friends.

Through pain ridden eyes the Swift Boat Skipper barely registered recognition and weakly whispered "How's Boyle? Is he

all right?" Gil replied "He's doing fine," which he wasn't. As the radio that the Americans carried began blaring questions

from the repair ship USS Krishna in An Thoi, the lights again went out for the young officer as he faded back

into unconsciousness.

Having assisted Johnson as best he could, the medic rigged a splint for Lloyd's badly broken left leg using an M-14

rifle. But the Swift Boat officer's weakened state worried LT Dunn, who started to ask the medic to check him out further,

but was interrupted by the arrival of the Dust-Off helo hovering overhead to take away the wounded.

| |

| |

Darkness was now fast approaching. Plus the weather and sea conditions had continued to deteriorate. So the junk was

rising and falling dangerously in the gloom as the helicopter moved in closer. Bob Johnson was the only one able to be loaded

onto the aircraft before the erratic pitching of the junk brought the helicopter's tail rotor blades much too close

and the rescuers had to wave it off. They tried again, the pilot settling his skids right onto the top of the junk's

cabin in an attempt to stabilize it. But again the seas were in control. The junk slipped out from beneath the skids

and, moving sideways, nearly careened into the deadly rotor-arc once again. The risk was too great. The mission had

to be aborted. |

By radio LT Dunn informed the helo pilot that PCF-3, which had now arrived, would be able to take the other two

wounded personnel on to Rach Gia, where an emergency hospital was available to provide urgent medical care.

Once the Americans were transferred to PCF-3, which headed at flank speed to the south, Gil looked down at Charlie

and found that the bleeding in his right leg had increased substantially. The medic quickly worked to apply a second

tourniquet. Charlie appeared to regain recognition of his surroundings, pointed at his heart and calmly said "I don't

hurt in my legs, Gil. I hurt in here." Since there was nothing more that Gil could do to care for either his friend or

David Boyle, he provided the only aid that might make a difference, and held tightly onto Charlie's hand to provide

comfort all the way back to Rach Gia.

With the help of some very dedicated US and Vietnamese sailors, airmen and medical personnel; both Bob Johnson and

Charlie Lloyd were quickly treated at the emergency medical facilities in Rach Gia and then loaded into a helicopter

to be transported to a more substantial hospital in Saigon. Recovering in the chopper from the anesthesia administered

on the treatment table, Ltjg Lloyd was relieved to see that his radioman was also being evacuated with him. Charlie's

crewman asked if his Skipper was OK.

| |

As darkness surrounded the sunken Swift Boat, the Navy and Coast Guard units converging on the ambush site began work

to organize an impromptu initial salvage operation, despite small arms fire from the shore. Overhead a flare ship,

UH-1 gun ships and an AC-47 Spooky began laying down a barrage of counter fire on the enemy positions. Other

arriving Swifts and a Coast Guard Cutter added their heavy caliber machine gun fire to that of the Yaubta to protect

a group of crewmen that were dropped into the water next to the stricken vessel to survey what could be saved or salvaged.

| |  |

|

Due to the few tools available and lack of visibility, they were only able to dismantle the boat's machine guns

before they had to retire. Throughout the rest of the night, Air Force gun ships along with the Swift Boats, Cutters

and Yabutas maintained harassment and interdiction fire on the shore line to insure that no one attempted to

reach PCF-4

At first light on the following morning, salvage crews again set to work despite the fact that the enemy was still close

by and active. The continued presence of air and sea borne resources to provide protective fire allowed sailors and divers

to once more enter the water to further assess ways to recover the sunken boat and its contents.

| |

|

A 20-ton mobile crane loaded on an LCM-8 borrowed from the civilian contractor Raymond-Morrison-Knudsen arrived from Rach

Gia around mid-morning. The crew on this vessel attempted to pull PCF-4 out of the water. But the hulk had settled too

deeply into the mud for the small crane's limited capability. The bridle attached to the boat was shifted and the LCM

tried to tow the boat away from the shore with little success. The Coast Guard cutter Point Mast then came

alongside also, with her screws just barely clearing the shallow bottom, and hooked up a second tow. PCF-4 shuddered,

rocked a bit and then began to slide along the bottom as both salvage boats strained in unison for increased pulling power.

As the protective machine gun fire from the close by Swifts, Cutters and Yabutas picked up tempo, the submerged PCF-4 was

dragged into deeper water some 2,000 yards off the beach and out of range of enemy small arms fire. Later she was towed

even further out to yet deeper water where larger salvage vessels would be able to move in and provide much greater lifting

capabilities

The repair ship USS Krishna (ARL-38) soon arrived to provide the necessary expertise and muscle needed to

complete the retrieval of the hulk that was now all that remained of PCF-4. These dramatic photographs document

the skill with which the sailors on the Krishna were able to accomplish that task.

| |

|

|

|

The above images courtesy of Ed Utley

PCF-4 was so catastrophically damaged that she would never sail again. But the aluminum cadaver was shipped to Subic Bay,

where it was carefully evaluated by engineers. Their analysis of the structural failures led to improvements in the hull

design that would reduce the vulnerability of all Swift Boats to being totally debilitated by mine-instigated attacks.

The lives of Swift Boat sailors on boats that would fall prey to enemy mines in the future were undoubtedly saved as a

result of the changes made to the structural integrity of the PCF hull. And like wise, the wide spread word of one of the

more sinister ways the enemy had of attacking US sailors most certainly prevented similar incidents from being repeated.

|

|

|

Bob Johnson came back from his injuries and requested a return to Swift Boat duty shortly thereafter. After a long

period of convalescence in the United States, Charlie Lloyd only partially recovered from the wounds to both of his legs.

They continue to affect his physical health even forty years later. He recently underwent his second hip replacement

and rearrangement of the pinned metal supports installed at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Washington DC in 1967. But it

is the pain of memories that keep on returning about that fateful day when the tragedy of war became all too real and

personal that affect Charlie the most. They simply will not go away.

|

|